Scientists use koala teeth to map Adelaide's history

If you want to know how Adelaide was settled by Europeans, you may need to look at rat and koala teeth.

A team of researchers from the University of Adelaide and Flinders University, used an interesting method of mapping Adelaide’s settlement: by looking at the build up of strontium isotope in the teeth of koala and rat remains.

Naturally occurring strontium is found in rocks and soil, and it can be absorbed into the body and bones. The ratio of strontium isotopes – variants of the chemical element – in bone is frequently used as an indicator of age, so this technique can show how long some bones have been in a certain area.

“Each location or geological area has very unique Sr isotope composition,” says Adelaide University researcher Juraj Farkas, an author on the paper, “which is related to its geological history and mineralogy”.

“These unique ratios will be ‘inherited’ in local groundwater (which leached these rocks) and thus also in local vegetation and plants growing in this area.”

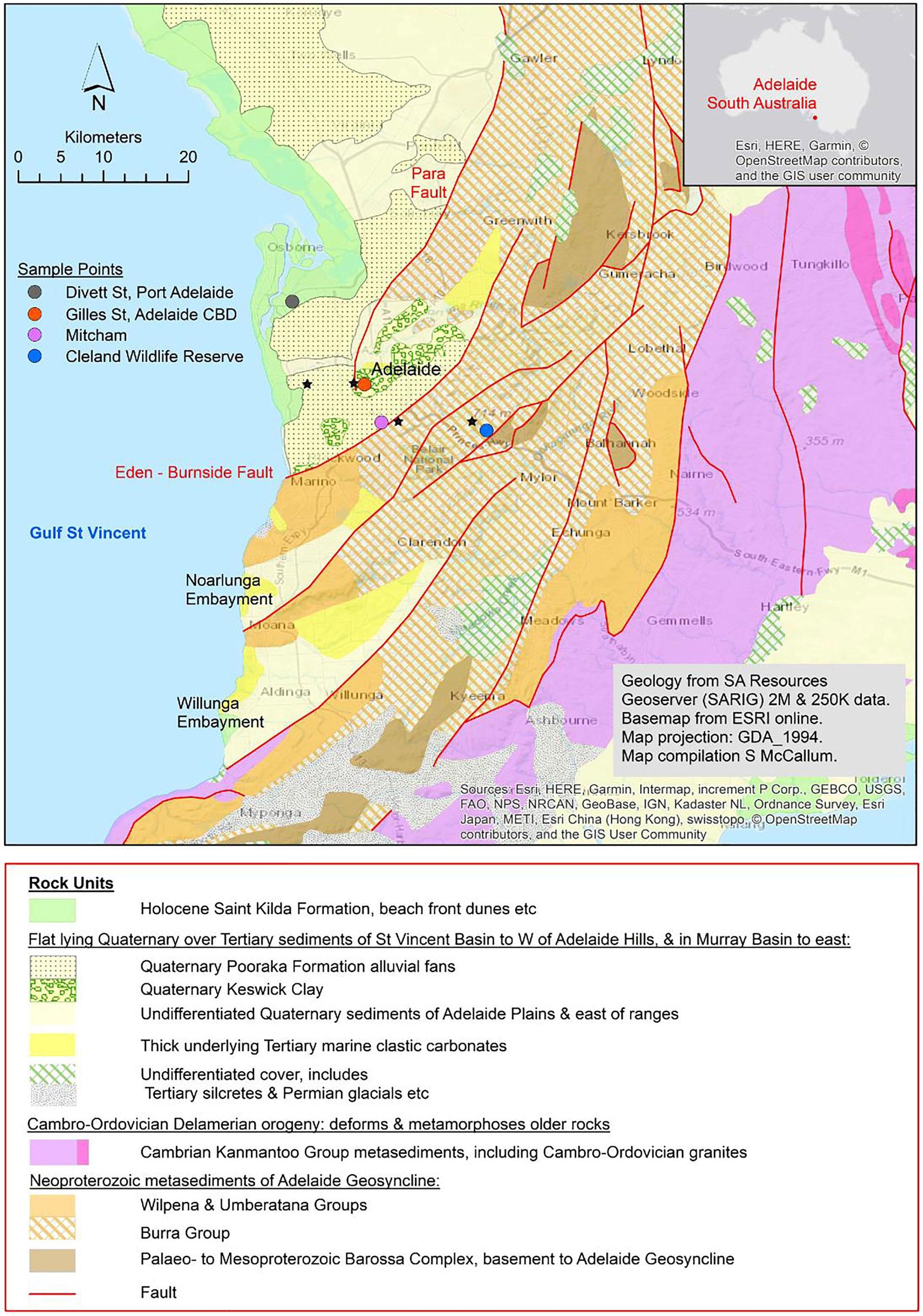

The geological formations relevant to this research and other formations with available strontium values. The four sample locations are shown as dots and the climate stations as black stars. View larger map.

The team used this technique to compare the strontium in teeth and bones with climate information from different locations around the Adelaide region, including samples from the Adelaide foothills, Adelaide airport, West Terrace (on Kaurna land) and Mount Lofty (on Peramangk land), to learn about the micro-climates of the past.

“Teeth are very resistant materials and will thus preserve really well their original Sr isotope composition, which in turn will reflect what plants or water sources this animal consumed during its life span,” says Dr Farkas.

“Sr isotope studies of teeth can help us to reconstruct in what areas this animal was living, plus it can also help to constrain migration pathways and movement of the animal or populations.”

“This study will create the basis for further investigations into the pre-European settlement of the Adelaide region, and help inform us about animals, plant life and weather before temperature and other climate records began,” says lead author Lee Ripon, of Flinders University.

This isn’t the first time strontium isotopes in teeth have been used to tell the time, but it is the first “tooth map” in South Australia. This could show more about the impact of European settlement on climate and landscape on Kaurna and Peramangk land.

Koalas used to live in the Adelaide region but became locally extinct after colonisation, sometime around 1930. They were reintroduced in 1959.

Comparing koalas and rats to humans is useful because both animals were heavily affected by European settlement – koala numbers dwindled, while rats prospered after their introduction.

They are also good comparisons because rats and koalas prefer to stay near home, and they experienced relatively little climatic change. This makes them ideal to study historic micro-climates.

“This analysis establishes a benchmark dataset against which previous studies of human (including Indigenous peoples’) tooth and bone samples can be contrasted,” says Dr Ian Moffat from Flinders University.

“The Adelaide area is ideally suited for the investigation of human and animal mobility employing stable isotope techniques; both because of the amenable geology and landscape and because of the nature of the archaeological questions that can be addressed in the region.”

The study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Further reading

- Baseline bioavailable strontium and oxygen isotope mapping of the Adelaide Region, South Australia, Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports

- This article, written by science journalist Debbie Devis, is republished with permission from Cosmos. View the original article.